What can we learn from the 6th edition of Canadian Best Practice Recommendations?

Authors: Victor Dabala, Oana Vanta

Keywords: Stroke, Rehabilitation, Recovery, Recommendations, Evidence

Focus keywords: Guidelines

Why do we need a stroke rehabilitation guideline?

What can we learn from the 6th edition of Canadian Best Practice Recommendations? With approximately 1 event in 4 persons, stroke remains the condition with the second highest mortality. As a complex healthcare burden that impacts millions, clinical elements like stroke-related guidelines must be elaborated to showcase the latest evidence-based information in an official context [1–3].

How important is a stroke rehabilitation guideline?

Current practices involving recovery after an ischemic stroke focus on the vital importance that (neuro)rehabilitation has in the whole process. While the management of the hyperacute and acute phases of stroke (consisting of assisting the vital functions of the patient, administration of intravenous thrombolytic therapy, and deciding what medications the patient should receive) is essential for stabilizing the stroke survivor, rehabilitation should be considered the further step [1, 4].

Therefore, a rehabilitation guideline should target the following issues (Figure 1) [1, 4].

As different rehabilitation guidelines focus on different aspects of stroke, it is sometimes relatively challenging to understand how a guideline system works, what should be the main points of interest, and how a guideline can ensure that its future editions will constantly improve in terms of science-based evidence.

Why should our attention be guided toward the Canadian Best Practice Recommendations?

A traditional instrument in stroke management, the Canadian Best Practice Recommendations is well-known for its focus on rehabilitation methods for moderate-to-severe strokes. Essential new aspects that were discussed in this year’s edition include:

- The use of systematic literature reviews (SLRs – along with the associated meta-analyses) as the main elements for obtaining valuable clinical information for the construction of the guidelines.

- The collaboration that should exist between all healthcare system parts, as a focused effort, demonstrated to improve results.

- Inclusion of the formal and informal opinions of different caregivers involved in stroke rehabilitation [1, 5].

The Canadian Best Practice Recommendations classify scientific data into three levels (based on the clarity of the evidence and the design of the research):

A level of evidence 🡪 data obtained from multiple RCTs and subsequent meta-analyses.

B level of evidence 🡪 Information from a single RCT or from observational studies.

C level of evidence 🡪 Results reported by a group of experts, expressing new, unreproduced results [1].

The Guideline system contains two different parts:

Part A explains the necessary components of a stroke rehabilitation system and the implementation

Part B explores the rehabilitation methods for multiple post-stroke impairments [1].

First things first – How should the assessment of a stroke patient look like?

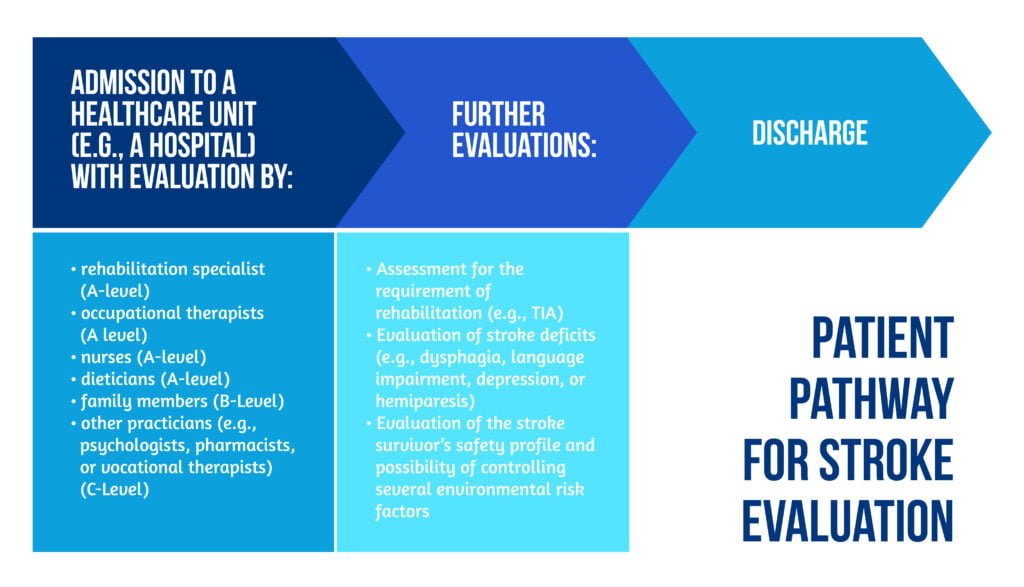

The assessment of stroke is a complex matter; therefore, the patient pathway for evaluation is presented in Figure 2 below.

Initial evaluation of the severity of the stroke and decision on the optimal moment of proceeding with the investigations are essential aspects that are always part of the process.

The assessment of the stroke patient should be started in the first 48 hours after admission, exploring:

- The patient’s functionality

- Their physical resources

- The intensity needed for the rehabilitation program.

If patients do not necessitate rehabilitation after the first assessment, they should furtherly be evaluated for the duration of the first month after the stroke (by performing weekly assessments). All previous aspects were graded with C-Level evidence [1, 5].

How important are stroke rehabilitation units? What about rehabilitation teams?

An appropriate location should be created for a stroke patient to receive proper rehabilitation. Stroke units should be made available in such a way that they cover most of the population from a territory (Level A).

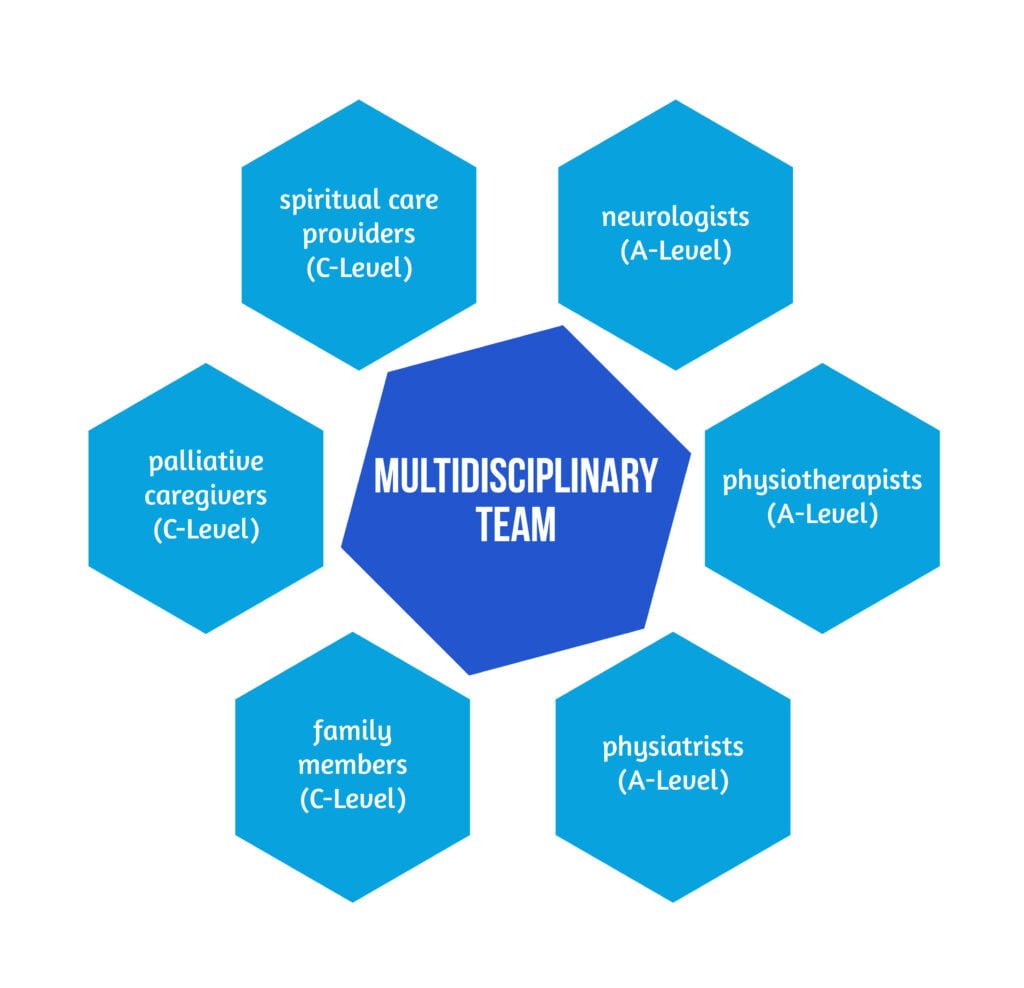

A multidisciplinary team should aid the patient, with potential members showcased in Figure 3 below:

Every week, the multidisciplinary team members should discuss the possibilities that each patient has for making progress, what are the most challenging aspects encountered, and how the available rehabilitation tools could be optimized for each patient.

The stroke survivor and their relatives should be informed of all the positive and negative aspects of a stroke, facilitating the educational aspects (A Level of evidence).

If admission to the stroke rehabilitation unit is not an option, a second possibility should be general rehabilitation units (Evidence Level B) [1].

How should inpatient rehabilitation be planned?

Rehabilitation should be started as early as possible after the patient has been stabilized and their functional capacity allows them to participate in recovery sessions. While an increased level of therapy facilitates faster recovery, the rehabilitation plans should be created in such a manner that it responds to the individual needs of every patient (Class A of Evidence).

Concepts like early mobilization or very early mobilization (VEM) were assessed in previous trials, generating mixed results [6, 7]. Regarding the time of mobilization, specific disorders like Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA) could benefit from the concept above, although more evidence is needed (Level C). Long-term, early mobilization should not always be selected as the first approach (Evidence Level A) [1].

The Canadian guidelines highlight the importance of the intensity of rehabilitation sessions with greater doses showing better scores on specific neurological scales (e.g., The Functional Independence Measure (FIM)) [1, 8].

After the patient regains a degree of independence, the next step should be the implementation of the reacquired skills and movements into more complex tasks (Graded with an A Level of Evidence). Each stroke survivor should benefit from at least 3 hours of daily task-oriented activities (Level A). Moreover, if the possibility of transferring the (re)acquired skills into the patient’s daily life exists, it should be applied [1, 8–10].

Is outpatient rehabilitation an optimal solution?

The 6th Canadian Best Practice Recommendations Guidelines continues the focus of its predecessors on the aspect of outpatient rehabilitation, being one of the few guidelines that include both inpatient vs. outpatient methods [1, 8].

Outpatient rehabilitation has several advantages, as it can be administered:

- At home

- In a specific community

- In specific care units

Although the differences between further inpatient rehabilitation and outpatient recovery are not significant, the latter has been proven superior to the absence of supplementary therapy (Level A) [1].

Out-of-the-hospital rehabilitation should be again provided by a multidisciplinary team specialized in the field of stroke (A-Class), encouraging the involvement of the patient and their relatives:

- Management of time and resources

- Self-setting of specific objectives

- Participation of the patient and the family in setting the procedure (Level A) [1].

When considering the time interval of outdoor rehabilitation, the Canadian Best Practice Recommendations comprise the following recommendations:

- At least 45 minutes daily (Level B)

- Two to five days each week (Level C)

- Approximately 2 months (Level C)

Starting the rehabilitation session 48, respectively 72 hours after discharge from inpatient recovery are both C-Level of Evidence recommendations.

Results from a 2019 analysis declared fast-track (FT) outpatient rehabilitation as a cost-effective method, providing an optimal level of rehabilitation and relieving the healthcare system [1, 11–12].

The 2019 Edition of the AHA & ASA Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery emphasizes the role that outpatient rehabilitation plays in the whole process, indicating that the procedures could be performed in a home healthcare agency (HHCA) or could be community-based. An important advantage of HHCAs is that they concentrate on multiple dimensions:

- Quality services in terms of general care and nursing

- Assuring different types of recovery for stroke survivors

- Assistance with specific daily tasks [13].

What recommendations should be applied for the management of upper extremity deficits?

As one of the most prevalent post-stroke complications (almost 75% of patients), upper limb deficits represent a significant cause of disability for stroke survivors. Although only a small percent of all the patients can describe a level of improvement, the situation seems different for mild-to-moderate deficits, with around 70% of stroke survivors experiencing an increase in motor function [1].

The therapies applied should be goal-oriented, and patients should be encouraged to use their affected limbs for simulated tasks or actions (Level A).

Several rehabilitation techniques were recommended as therapies with a high level of evidence (Level A Grading):

- Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES)

- Mirror therapy

- Constraint-induced movement therapy

- Virtual reality techniques

- Strength training.

Although the Canadian guidelines offer a comprehensive picture of recovery methods, some important aspects are more clearly emphasized in other guidelines (e.g., AHA/ASA Guideline for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Guideline), such as:

- The management of post-stroke pain and the disorders that could be the cause of the pain (e.g., shoulder-hand syndrome)

- The significant effect played by the general loss of lean mass after a stroke

Other examples, like bilateral arm training, possess an important level of evidence that they should not be preferred over others (Level A) [1, 13].

How can we refer to the rehabilitation of the lower limb?

A multitude of disorders targeting the lower limb can occur after a stroke, including:

- Gait disturbances

- Loss of balance

- Impaired motor function.

While more than a third of patients are unable to recover a proper level of independence, more than a quarter of survivors cannot walk independently after a stroke [1].

As goal-orientated tasks (Class A of Evidence) are becoming more familiar with the different models of rehabilitation, different examples are discussed in the Canadian Best Practice Guidelines, as described in Figure 4.

The Canadian Guidelines consider all the previously mentioned methods as Class A recommendations [1].

Conclusions

Being a continuously updated clinical instrument, the 2019 Edition of the Canadian Best Practice Guidelines comprises a vast amount of clinically relevant information, facilitating the creation of a connection between different stroke aspects, including the setting of the rehabilitation procedures and the clarification of the inpatient-outpatient possibilities of recovery [1].

In contrast to other guidelines, the Canadian Best Practice has continued to update with each edition (the first edition was published more than 6 years ago), including the most recent and comprehensive information for different stroke aspects (e.g., rehabilitation methods for the upper and lower limb). The main advantage of the Canadian Guidelines is the detailed presentation of all the possible recovery measures and therapies, also focusing an important part of the context on the inpatient-outpatient relationship in rehabilitation [1].

Compared to one of the most important pieces of work in the domain of neurorehabilitation (the AHA/ASA Guideline for Rehabilitation in Adults), the current edition of Best Practice Recommendations could benefit from additional content (e.g., acute and chronic stroke complications or the management of post-stroke pain syndromes) or a more detailed approach regarding both primary and secondary prevention (e.g., a more complex chapter explaining the importance of controlling risk factors could be an essential addition) [1, 13].

As a helpful instrument in properly administering rehabilitation for stroke survivors, the Canadian Stroke Guidelines should be paired with primary and secondary preventive strategies, creating a complete approach to stroke assessment.

References

- Teasell R, Salbach NM, Foley N, Mountain A et al. Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Rehabilitation, Recovery, and Community Participation following Stroke. Part One: Rehabilitation and Recovery Following Stroke; 6th Edition Update 2019. Int J Stroke. 2020 Oct;15(7):763-788. doi: 10.1177/1747493019897843.

- Lindsay MP, Norrving B, Sacco RL et al. World Stroke Organization (WSO): Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2019. Int J Stroke 2019; 14: 806–817. DOI: 10.1177/1747493019881353

- Feigin VL, Norrving B and Mensah GA. Global burden of stroke. Circ Res 2017; 120: 439–448. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308413

- Graham ID, Harrison MB, Brouwers M, Davies BL and Dunn S. Facilitating the use of evidence in practice: evaluating and adapting clinical practice guidelines for local use by health care organizations. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2002; 31: 599–611. DOI: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2002.tb00086.x

- Cameron JI, O’Connell C, Foley N et al. Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: managing transitions of care following Stroke, Guidelines Update 2016. Int J Stroke 2016; 11: 807–822. DOI: 10.1177/1747493016660102

- AVERT Trial Collaboration group. Efficacy and safety of very early mobilisation within 24 h of stroke onset (AVERT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 46–55. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60690-0

- Sundseth A, Thommessen B and Ronning OM. Outcome after mobilization within 24 hours of acute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2012; 43: 2389–2394. DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.646687

- Dromerick AW, Geed S, Barth J, Brady K et al. Critical Period After Stroke Study (CPASS): A phase II clinical trial testing an optimal time for motor recovery after stroke in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 ;118(39):e2026676118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2026676118.

- Wang H, Camicia M, Terdiman J, et al. Daily treatment time and functional gains of stroke patients during inpatient rehabilitation. PM R 2013; 5: 122–128. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.08.013

- Imura T, Nagasawa Y, Fukuyama H, Imada N et al. Effect of early and intensive rehabilitation in acute stroke patients: retrospective pre-/post-comparison in Japanese hospital. Disabil Rehabil 2018; 40: 1452–1455. DOI: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1300337

- Tam A, Mac S, Isaranuwatchai W, Bayley M. Cost-effectiveness of a high-intensity rapid access outpatient stroke rehabilitation program. Int J Rehabil Res. 2019 Mar;42(1):56-62. DOI: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000327

- Schneider EJ, Lannin NA, Ada L and Schmidt J. Increasing the amount of usual rehabilitation improves activity after stroke: a systematic review. J Physiother 2016; 62: 182–187. DOI: 10.1016/j.jphys.2016.08.006

- Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, Bates B et al. Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47(6):e98-e169. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000098. Erratum in: Stroke. 2017 Dec;48(12 ):e369. DOI: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000098