The effectiveness of intense neurorehabilitation of the upper limb after stroke

Authors: Irina Benedek, Oana Vanta

Keywords: stroke rehabilitation, intensive neurorehabilitation, upper limb rehab

Introduction

Despite the recent progress in reperfusion therapies, several stroke patients still suffer from significant deficits beyond the acute phase. Therefore, neurorehabilitation is crucial for overall comprehensive recovery. Long-term neurorehabilitation is a continuously expanding field and is appropriate in a multidisciplinary center under the careful supervision of physicians, specialized therapists, and nurses [1].

Impairment of the upper limb is one of the most common motor deficits that this category of patients is likely to experience and an essential contributor to persistent physical disability [2]. Stroke represents one of the lead causes of this health issue worldwide, with more than 80% of affected people experiencing this condition in the acute phase and over 40% chronically [3].

The most common symptoms of motor limb impairments are:

- Muscle weakness or contracture

- Changes in muscular tonus

- Impaired motor control

- Joint laxity [3].

The conditions mentioned above significantly impact daily activities such as holding, reaching, or picking up objects and reduce the overall quality of life [3].

Recovery after stroke

One of the most common questions asked by most patients is: “Will I get better and when?”

The most crucial part of long-term recovery was reported in the first three months after a cerebrovascular event, even though scientific data proves that neurorehabilitation is not limited only to this time frame [2]. However, it is important to mention that improvements are likely to be slower in the chronic phase of stroke. Essentially, stroke rehabilitation targets “relearning” different functions rather than recovery itself [4]. Thus, longer and more intense specific rehab programs were proposed to improve outcomes. However, there are some limitations of clinical trials in this matter. Up until now, they did not deliver a significant impact in improvement that could provide changes in current clinical practice. A common issue in these trials was that the dose, quantified in additional therapy hours, remained low (18-36 hours). For instance, one study delivered data from 300 hours of rehab in the chronic phase of stroke patients who presented upper limb deficits that were far greater than the average [2, 5].

As this issue deserved further investigation, “The Queen Square Upper Limb Neurorehabilitation Programme” offered 90 hours of therapy for chronic post-stroke patients who reached over six months after the acute event. The research reported data for people included in this program to assess whether any clinical improvements were maintained and to establish if there was a connection between activity and changes in motor deficits [2].

Patients’ eligibility

If the investigators considered that they could bring a significant change for the better in patients’ outcomes, almost every stroke patient was included. However, there were some clinical limitations to admission, such as:

- complete plegia of the affected limb with no movement present whatsoever

- pain in the shoulder joint which was likely to limit active movements

- important post-stroke spasticity

- other severe medical conditions [2].

Even though this category of patients could not benefit from the program, they were advised and guided to other more suitable medical services.

The minimal admission requirements were at least the capacity to flex the shoulder or slight movements in the fingers or wrist extensor muscles. Several tasks were implemented to improve the quality of movement, focusing on adapting the chore to individual needs, independent task practice, assistance, and improving the environment where the physical therapy took place. Coaching was a crucial component of the program. Therefore, participants increased their motivation and confidence in their long-term recovery goals [2].

Evaluation tools and neurorehabilitation programs used

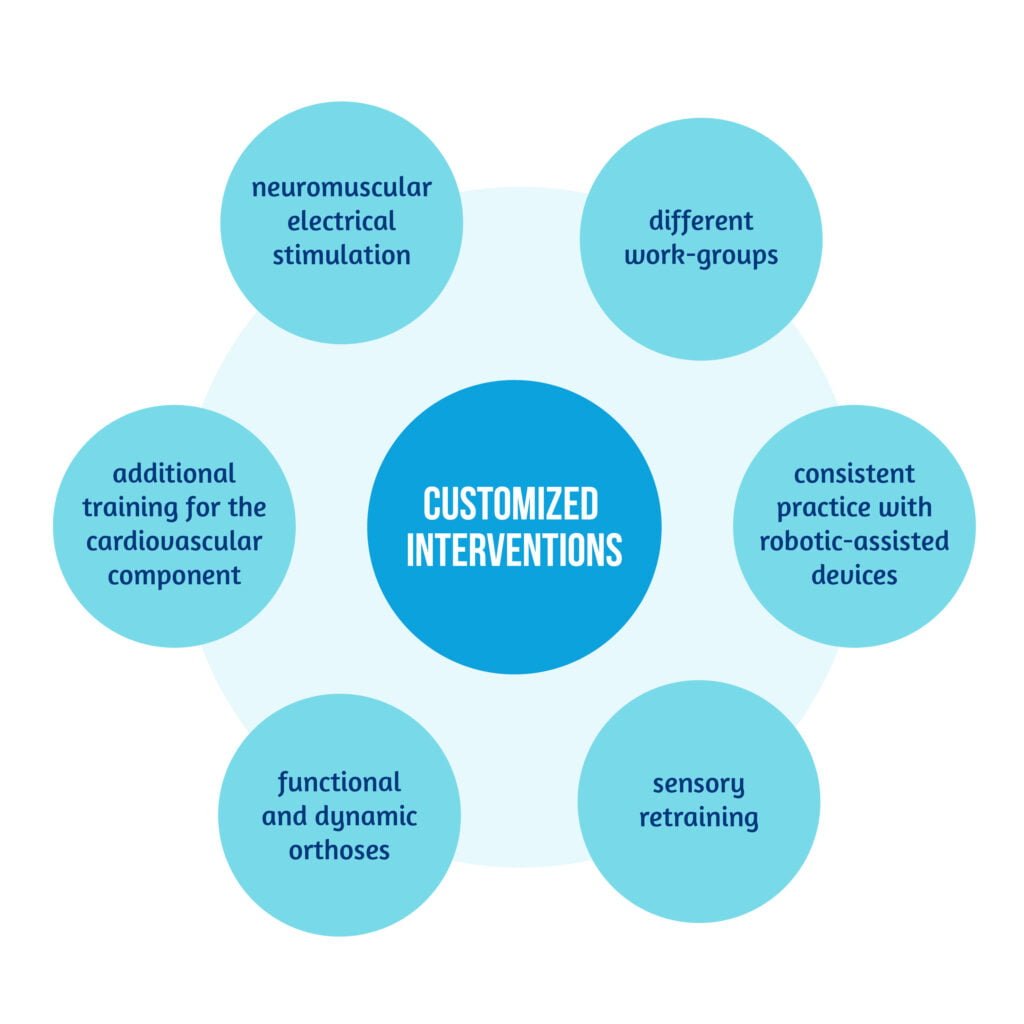

The overall approach consisted of two daily sessions of physical therapy and occupational therapy with customized interventions when needed, such as the ones described in Figure 1 below [2]:

The program was designed as a one-to-one, one-patient-to-one medical professional, six hours a day, five days per week for three weeks, to obtain the best results possible. Several parameters were tested at baseline (T1), which were later reevaluated at discharge (T2), at six weeks (T3), and six months after discharge (T4) [2]. The most important scales used to quantify the neurological impairment and improvement are represented in Table 1:

| Scale | Assessment focus | Type |

| “The Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA)” | – motor and joint functioning – balance – sensation | performance index |

| “The Action Research Arm Test (ARAT)” | – functioning – dexterity – coordination | observational |

| “The Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Inventory (CAHAI)” | – recovery | quantitative supports the use of both arms |

| “Arm Activity Measure (ArmA)” | – use of the arm in daily tasks – ability to use the unaffected limb to help take care of the impaired one | questionnaire |

Besides these specific items, classical neurological evaluation tools were also assessed at admission, such as:

- Barthel Index (BI)

- Modified Rankin Scale (mRS)

- Neurological Fatigue Index (NFI)

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

- Sensation-tested along with the Fugl-Meyer scale.

The main goal was to quantify the changes in the impaired upper limb and evaluate if the baseline results correlated with the final outcomes [2].

Essential results of the study

All patients were able to finish the program successfully and completed the 90-hours physical therapy. The study consisted of 268 patients and took place between January 2015 and December 2017. It is essential to mention that 16 persons were admitted earlier than six months after stroke, and only one sooner than three months. From a total of 238 stroke patients, 224 completed the follow-up assessments established in the program. Some subjects experienced difficulties, mainly correlated with fatigue symptoms. The most important outcome was that significant changes in the upper limb function were noted with an improvement of the monitored parameters and correlated significantly with the baseline. These changes were also noted at the six-month follow-up, and some of them improved even more (see Figure 2).

The initial neurological impairment was the crucial factor influencing the recovery rate [2].

The QSUL Programme relied on the hypothesis that intensive neurorehabilitation in the chronic phase of a cerebrovascular event can significantly improve the outcome of this category of patients [2].

The results obtained in this study after the 90-hours program were very similar to those who used even more intensive physical therapy, with an improvement in the FMA of 9 points at the six months follow-up [2, 5]. The results were promising, mainly due to the heterogeneity of patients included and the wide range of motor impairments [2].

Predictive factors

Even though the perspective of regaining almost complete function of a previously impaired limb is brightening, some limitations still need to be considered. Understanding specific predictive factors of recovery is essential. It allows medical workers to adapt and individualize the therapeutic plan and provide proper guidance to the patients and caregivers. Even though results differ for every patient, some studies report that upper limb function at four weeks and three months are highly predictive of overall recovery at six months.

The best predictive factors of regaining motor function after a cerebrovascular attack are related to the extent of cerebral lesions as seen on neuroimaging and functional deficits, as represented in Figure 3 [4]:

Long-term complications

Unfortunately, except for motor complications, several other risk factors are likely to persist in the long term, such as:

- severe spasticity with contractures

- deep vein thrombosis

- hand-shoulder syndrome

- different grades of edema.

Implementing rapid measures to prevent spasticity plays a significant role in avoiding disabling complications [4]. Using intensive neurorehabilitation programs to prevent chronic complications is somehow challenging in the setting of clinical practice, in part because of the logistics implied, and partly because of the reluctance of clinical practitioners to accept this path of action.

Conclusions and perspectives

Even though stroke remains the leading cause of morbidity and disability worldwide, there are still ways to prevent long-term disabilities. Studies show relevant data and promising results in the rehabilitation of the motor function, even in the chronic phase of this disease. Developing individualized, intensive recovery programs for patients can provide great success in achieving the desired goals.

Although the results are exciting, it is vital to consider the study’s limitations and that the data was obtained from a single-center medical unit. Still, it was proven that increasing the intensity and duration of physical therapy, specifically designed for each patient’s needs, can bring further benefits to the long-term upper limb recovery [2].

References

- Anaya MA, Branscheidt M. Neurorehabilitation after stroke from bedside to the laboratory and back. AHA Journals.org 2019;50:e180–e182. DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023878

- Ward NS, Brander F, Kelly K. Intensive upper limb neurorehabilitation in chronic stroke: outcomes from the Queen Square programme. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2019;90:498-506. DOI: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-319954

- Hatem SM, Saussez G, Della Faille M, Prist V et al. Rehabilitation of Motor Function after Stroke: A Multiple Systematic Review Focused on Techniques to Stimulate Upper Extremity Recovery. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:442. DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00442

- Tsu AP, Abrams GM, Byl NN. Poststroke upper limb recovery. Semin Neurol. 2014 Nov;34(5):485-95. DOI: 10.1055/s-0034-1396002

- McCabe J, Monkiewicz M, Holcomb J, Pundik S et al. Comparison of robotics, functional electrical stimulation, and motor learning methods for treatment of persistent upper extremity dysfunction after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:981–90. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.10.022