The importance of physical activity in neurorecovery

Authors: Irina Benedek, Oana Vanta

Keywords: physical activity, walking, stroke, acquired brain injury

The importance of physical activity in neurorecovery

Worldwide, 5 million of the 16 million people who suffer from strokes each year end up having to deal with a certain degree of disability as a consequence [1]. Stroke is the most significant cause of long-term impairment in the elderly and is frequently followed by infirmity. A third of those who experienced a stroke are expected to have another one within five years, placing patients with this pathology at high risk for subsequent cardiovascular events [2].

Physical activity (PA) is defined as any skeletal muscle-driven motion of the body that needs an energy expenditure [3]. Exercise is a kind of PA that is deliberate, ongoing, and intended to enhance body functions.

It is generally known that stroke survivors are less physically active than the general healthy population, with around half the daily step count and fitness levels below the national norm for their age. Additionally, acquired brain damage (ABI) has been associated with low aerobic capacity. Even though it has been proven that consistent PA of at least moderate intensity reduces the risk of stroke, reaching adequate PA levels for patients suffering from these pathologies has been challenging.

If people who had a stroke or an ABI are to be helped in reaching the necessary levels of PA, it is essential to understand why they are less active than their healthy peers. Understanding the challenges and positive factors that encourage PA after a stroke or ABI is essential, even at an early stage [2]. Physical functioning recovers more quickly after a stroke if rehabilitation is started quickly, and there is a greater probability that PA levels will remain stable [4].

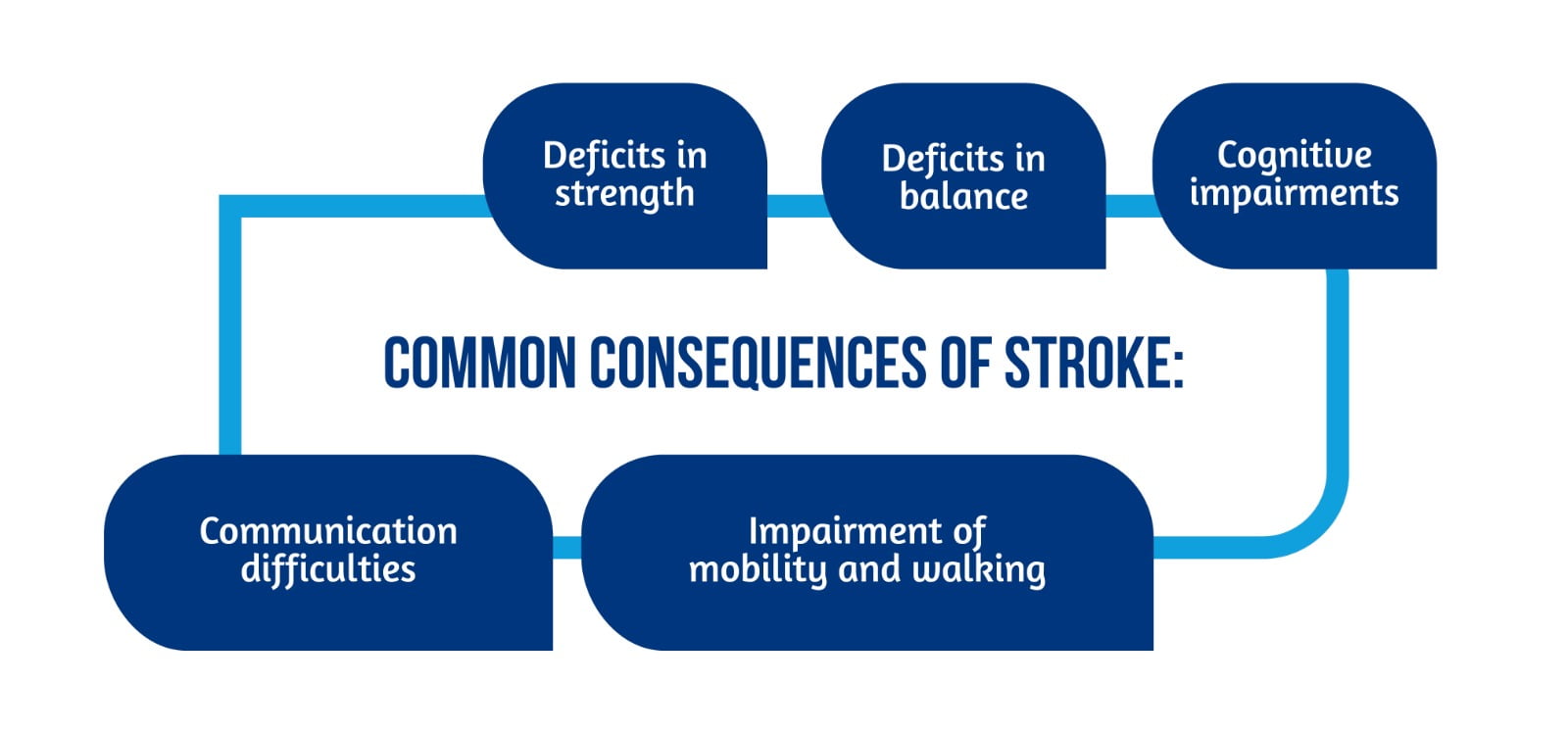

Some of the most common consequences of stroke include the ones showcased in Figure 1 [2].

Improving mobility and walking capacity is the stroke-related deficit that stroke survivors rate as the most important. As a result, gait recovery is listed as the most common rehabilitation objective [2].

Significant global attempts have been made to identify evidence-based rehabilitation methods to enhance stroke recovery. Despite these initiatives, it is still unclear how to adopt and maintain PA for people with a stroke or ABI. It is mandatory to look at how people with stroke perceive PA and walking, a very new, emerging, and crucial area of study, to find the answers to these concerns. Although qualitative research tries to comprehend perspectives on PA as well as obstacles and facilitators after stroke, there is little information available regarding experiences of walking post-stroke [5, 6].

A recent study by Törnbom et al. investigated how people with acquired brain damage or stroke felt about walking and physical activity in general [2].

Study participants and evaluation

In terms of distribution by age, sex, and severity of the disability, participants were deliberately selected by a physical therapist to reflect the actual rehabilitation population relying on specific criteria (Figure 2) [2].

The Fugl-Meyer Assessment of motor function in the lower extremities [7] and the 30-meter walking test [8] were used to determine the comfortable walking pace. The study comprised eight stroke survivors (n=8) and two survivors of acquired brain injuries (ABI) with comparable symptoms (n=2). All of them were enrolled in intense team therapy between two and ten months following the onset of their symptoms. The participants’ ages ranged from 38 to 64. Participants were encouraged to ambulate outside the hospital as part of the recovery program, with or without assistance [2].

The assessment was performed through patient interviews, which lasted from 19-61 minutes with a mean time of 36 minutes and were audio-recorded. Each interview started with the participants filling out a questionnaire, the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE), which asked them to list their recent physical activity. Then, for researchers to understand the context from which their personal experiences and views originated, they asked them to recount the incident that caused their injury.

Study outcomes

All patients responded positively when discussing the concept of PA in general before stroke or acquired brain injury; PA was connected to well-being and good health [2]. All patients’ characteristics and physical activity scores can be identified in Table 1.

However, participants’ accounts of PA before stroke or ABI varied significantly. Three participants emphasized how significant PA had been in their lives and how much they now missed it. They had been exercising, playing different sports, and lifting weights. Others claimed to be largely inexperienced when it comes to physical activity. Some people who have previously exercised throughout their lives stopped due to physical limitations, lack of interest, or lack of time. Exception for one person, everyone thought that short walks to the store or bus stop qualified as exercise [2].

| Sex | Age (yr) | Diagnosis | Time since onset (months) | Motor function FMA-LE | Comfortable walking speed (m/s) | Walking aid | PASE score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| male | 53 | Stroke | 6 | 34 | 1.28 | none | 79 (39) |

| male | 45 | encephalitis | 2 | 34 | 1.11 | none | 28 (19) |

| male | 38 | cerebral trauma | 5 | 34 | 1.56 | none | 114 (-) |

| female | 41 | Stroke | 7 | 34 | 1.36 | none | 62 (44) |

| male | 64 | Stroke | 3 | 34 | 1.36 | none | 70 (43) |

| male | 51 | Stroke | 6 | 21 | 1.07 | stick | 57 (28) |

| male | 50 | Stroke | 4 | 20 | 0.58 | stick | – |

| female | 53 | Stroke | 2 | 34 | 1.25 | none | 51 (30) |

| male | 62 | Stroke | 8 | 32 | 1.29 | none | 27 (16) |

| female | 42 | Stroke | 10 | 18 | 0.68 | stick | 34 (19) |

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics and physical activity scores, available from [2].

Perceptions of walking and overall physical activity after stroke or ABI:

- Negative perceptions of PA: After a stroke or ABI, PA was said to be required to recover and prevent a further cardiovascular event. Participants perceived PA as demanding and unappealing at the same time; it was essentially defined as a “necessary evil” [2].

- Lack of engagement with PA: Participants revealed that they did not engage in other types of PA besides their recovery program. The majority of them only walked a few hundred meters to a few kilometers on average per week, according to reports.

- Frustration with the recovery process: Several individuals shared their goals for their future fitness routines. These goals were accompanied by frustration about the perceived slowness of the recovery process [2].

- Difficulties in the rehabilitation process: Participants believed they could not walk the same way they used to in the past. They were moving more slowly, it was difficult for them to walk straight, and they constantly stopped to catch their breath. Most patients feared falling, and some had coordination and muscle weakness issues. In other instances, troubles with balance and walking were linked to diplopia or reduced vision [2].

- Lack of motivation and energy: Patients also described why they did not feel motivated or had the energy to walk or do PA. One of the primary issues raised was exhaustion and other concerns like lethargy, depression, and an overall lack of initiative. Several participants said they occasionally felt worn out, could not manage to leave the house, and occasionally had to push themselves to get up from the couch [2].

- Anxiety related to physical activity: Participants stressed a need to feel secure during the actual exercise; therefore, they requested advice about how to exercise safely. A few also wanted someone to accompany them because they feared falling. Moreover, participants wanted to perform an exercise they enjoyed and feel well after exercising [2].

- Environmental factors influenced physical activity: Participants talked about how being overly aware of their surroundings could be quite unsettling and make moving difficult. A distressing input might be auditory, visual, or potentially dangerous situations (traffic). Too much input when walking can produce severe balance issues and exhaustion, making the situation unpleasant and occasionally frightening. The participants acknowledged that maintaining a straight gait and a steady pace required substantial concentration. Another inconvenience that increased the chance of falling or losing one’s equilibrium was bad weather. When there was a chance of sliding, raining, or snow on the ground, many individuals chose not to walk.

Discussions and conclusions

An interesting finding of the study of Törnbom et al. was that while all participants considered PA essential to obtain good health, walking or PA was simultaneously associated with different negative feelings and experiences. Regardless of participants’ exercising habits pre-stroke, PA was defined as difficult and joyless after a stroke. Additionally, there was anxiety about not walking =”like everyone else,” which may have been a worry about coming off as someone with a handicap. This result was consistent with research from the USA, where individuals wanted to walk more easily and with better coordination to avoid stigmatization [2]. These findings highlight the importance of social support in the neurorecovery of this category of patients.

Previously, different facets of social support and its significance were examined. For most participants, being accompanied by someone, being encouraged to exercise, or having a scheduled visit to the rehabilitation facility was crucial. They gained encouragement, optimism, and more reasonable aspirations after meeting others in similar circumstances. The hospital’s rehabilitation staff was praised, and patients acknowledged and voiced concern about what would occur when their rehabilitation program had to end – many said that once this social and professional support was gone, they might not exercise at all [2].

Participants frequently used the words “general physical activity” and “planned exercise” interchangeably. A previous qualitative study that aimed to explore these issues has proven the problem that the terms “exercise” and “PA” are not clearly defined and that mixed notions are used instead, which can generate confusion [2].

It is essential to note that individuals who stated that PA had been a significant aspect of their lives before having a stroke did not enjoy PA in any way after the cerebrovascular event and had to utilize motivational techniques; furthermore, they stated that were even more or less coerced by others to participate in PA. The participants in the current research were considerably younger, with a mean age of 50 years. One could have anticipated that they would be more motivated to participate in PA to restore functionality in daily life and return to work [2].

Since the participants had a lower mean age than the general stroke population and quite good communicative ability, the results may be less representative of the whole stroke population. Another limitation is that the study did not include a measure of cognitive function. The fact that both categories of patients with stroke and ABI were included makes interpretation for a specific patient group difficult. However, this mix of diagnoses was considered reasonably representative of the population in the rehabilitation unit [2].

The current study revealed that stroke and ABI patients need therapy that includes teaching coping mechanisms for exhaustion and other issues related to neurorecovery that they might experience. Addressing these issues is essential to encourage these patients to participate in PA. Facilitating individual motivation and commitment throughout the recovery process may be another hurdle for physical therapists and other healthcare practitioners. Families’ involvement can be crucial in addressing the need for additional external motivation. Future studies should concentrate on developing rehabilitative strategies based on the concerns these groups had with PA and assess the strategy’s efficacy [2].

For more information on neurorehabilitation, visit:

- Intrinsic Mechanisms of Acupuncture in Ischemic Stroke RehabilitationRobotic neurorehabilitation for the upper limb – new insights

- Efficacy of placebo in managing pain for neurological disorders

- Neurorehabilitation in dystonia – a holistic approach

We kindly invite you to browse our Interview category: https://efnr.org/category/interviews/. You will find informative discussions with renowned specialists in the field of neurorehabilitation.

Bibliography

- Billinger SA, Arena R, Bernhardt J, Eng JJ, et al. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2014;45(8):2532–53. DOI: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000022

- Törnbom K, Sunnerhagen KS, Danielsson A. Perceptions of physical activity and walking in an early stage after stroke or acquired brain injury. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0173463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173463

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/.

- Mead GE, Greig CA, Cunningham I, Lewis SJ et al. Stroke: a randomized trial of exercise or relaxation. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55(6):892–9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01185.x

- Resnick B, Michael K, Shaughnessy M, Kopunek S, et al. Motivators for treadmill exercise after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2008;15(5):494–502. doi: 10.1310/tsr1505-494

- Salbach NM, Veinot P, Rappolt S, Bayley M, et al. Physical therapists’ experiences updating the clinical management of walking rehabilitation after stroke: A qualitative study. Physical Therapy. 2009;89(6):556–68. DOI: 10.2522/ptj.20080249

- Fugl-Meyer AR, Jaasko L, Leyman I, Olsson S, Steglind S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975;7(1):13–31. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1135616/

- Witte US, Carlsson JY. Self-selected walking speed in patients with hemiparesis after stroke. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1997;29(3):161–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9271150/